Brewed with boiling water from the silver samovar, the tea was brought at any time of day by the provodnitsa assigned to our carriage. We called her the tea lady and admired her brightly colored Russian scarf.

Everyone drank the tea, including my three-year-old sister and me. No wonder we never slept on that train, although it was our first time sleeping on a top bunk! Strong, boiling hot and served in tall glasses placed in metal holders with handles, the tea was accompanied by large, rectangular blocks of sugar to take away the bitterness. Two sugar blocks per cup, except children were allowed more. The tea took away some of the chill as well. Every carriage had its own wood-fired stove for heat and for cooking, but early spring in Finland is still cold and snowy and the train was barely warm. The steam locomotive was noisy and had a snowplow. It made a big impression arriving in the Helsinki station.

We had permission and special visas to join a group of those privileged Finns allowed to go to Russia during the Cold War years: people doing business there, or families separated from Russian relatives who hadn’t been allowed to leave the country during wartime. It was Easter 1972, and we children had a week’s break from school and my father from his Fulbright professorship work at the University of Oulu.

We drank the strong tea and ate dark bread, cheese, and boiled eggs with our traveling companions, another young American family. Our friends’ boy, around my age, had never eaten a hard-boiled egg before and asked me for help. I showed him how to crack the shell and peel it away. Not liking the look or taste of the white of the egg, he peeled that away too and was left with the yolk. In the end, he wouldn’t eat the yolk either. Although only six, I was shocked at his carefree attitude toward wasting food. I don’t think the tea lady was too happy either.

The train chugged through the countryside from Helsinki to Leningrad, not stopping to let anyone off or on. Suddenly it slowed to a stop in the middle of a forest before we had reached the border. To our alarm, Russian soldiers with Kalashnikov rifles climbed on board and went through every carriage. Despite having grown up in Western Montana, I had not yet seen a gun, and certainly not an AK-47. The soldiers walked through the train, confiscating purses, magazines, and anything that looked Finnish, even our toys and Marimekko-designed coin purses. We held back tears. At the border our train was hooked up to a Russian train for the remainder of the journey. Upon our arrival in Leningrad, the soldiers walked back through the train and unexpectedly made us smile as they gave back most of the passengers’ possessions, including our coin purses.

Walking into our large hotel room in the city, all green and gold inside, with views through large windows of gold and colored enamel domes everywhere we looked, we stepped back in time to the eighteenth century. The room was cleaned by a fellow who waxed the dark wood floor every day. But the huge, marble, kitchen-like sink had cold water only. And there was no toilet paper, just brown paper. For my three-year-old pampered sister, this was cause for tears and protests. So off our mother went, dragging both of us along, to try to rustle up something closer to American toilet paper. And sure enough, a kindly woman took pity, opened a desk drawer, and handed our mother a few sheets of rough toilet paper bought on the black market. My mother gave her some coins, although doing so was against the rules, so each time she saw us coming back to our room she immediately opened the drawer for sheets of the precious toilet paper. Sometimes she smiled.

We waited in a long line on the street just to buy two small, wrinkly apples for about a dollar apiece.

Several older women dressed in woolen coats, shawls, and knit hats also waited patiently near us in the line. Two or three of them, with smiles and hugs, offered sweets to me and my sister. Of course there were souvenirs to buy in the shops: a balalaika, nesting dolls, wooden spoons. These are still in our family.

We had heard that people on the street might try to buy our clothes, particularly our American jeans. Or maybe my father’s feral dog-fur hat.

It turned out that our Finnish Nokia rubber boots were more attractive, in these years when everyday items we took for granted were difficult for ordinary Russian citizens to obtain. Our bright, primary-colored boots were not only eye-catching in the grey Nordic climate, but sturdy, waterproof and well-insulated against the cold. We had much tramping around to do on wet streets in our one short week and did not part with the boots. Anywhere we could go on foot, we went.

We were off to the Russian Admiralty, then the Winter Palace, site of the Hermitage Museum, where our little hands had to be restrained from touching the profusion of gold objects everywhere we looked. But what was this giant, ornate silver box towering over us, bigger than a bathtub, that looked big enough to hold a body? Sure enough, it was the sarcophagus that had held the body of St. Alexander Nevsky, the legendary medieval prince and military hero later canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church.

After the Hermitage, we went to Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral in the fortress on the Neva River, the city’s oldest building, which somehow miraculously survived the Siege of Leningrad. The cathedral is a rather large place for two small girls to explore without needing a break, and inevitably my sister said she needed to go to the bathroom. Someone led us down winding stairs to the basement of the cathedral and pointed to a hole in the ground. My sister took one look, turned around and ran back up the stairs screaming, “I don’t have to go anymore!” Nothing would convince her to squat over a hole beneath the tombs of all the Russian czars.

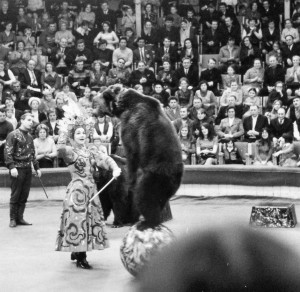

Another day we went to the Mariinsky Theatre to see Prokofiev’s last ballet, The Stone Flower, but a folk tale in four acts, no matter how interesting, proved too long for small children trying to stay awake in the late afternoon in a dark theatre. The Moscow Circus was the highlight of the week. No chance of falling asleep during the four-hour show: daring aerial acts, a tightrope walker with no net beneath the rope, acrobats jumping from one galloping horse to another, and the famous clowns.

In those years when circuses included trained wild animals, there were also black bears jugging, dancing, and balancing on tall poles and large balls.

No story about Russia would be complete without mention of vodka. At a luncheon of traditional food such as borscht, bread, eggs, and custards, there were frequent vodka toasts to “the Americans”, and of course to the Russians there as well. Stand up, toast, drink, sit down. Repeat, over and over. It took some explaining by our parents to understand why people were popping up and down so often. There was also a rather crowded cocktail party hosted by some Americans who lived in an interesting, dark apartment with high ceilings. We children were settled in a back room to read, play games and study the Cyrillic alphabet. I suspect we fell asleep.

But I come back to my strongest memory, for to this day, the Russian tea served on the train is the strongest tea I have ever had.

Photos: Coburn and Mona Freer

BIO: Meg Freer grew up in Montana and lives in Kingston, Ontario. She has worked as an editor and currently teaches piano and music history. She enjoys running and being outdoors year-round and wishes she had more time for writing poetry. Her writing has been published in various journals and anthologies.

Keep Reading! Submit! Inspire Others…

If you enjoy these travel stories, please donate $5… We’re committed to remaining advert-free and so your support makes all the difference. Thanks again.

$5.00

If you have stories of your own that you’d like to submit for possible publication, please do!