‘Download completed,’ announced the hoary computer in the business centre of Hotel Lalibela in Addis Ababa, after sputtering for what seemed like ages. When I clicked Open and a reassuring language appeared on the screen, I let out a small cry of triumph: I had finally gotten my hands on an English translation of the Kebra Nagast [1]. The long-legged reception lady with short raven hair, who had kindly reopened the tiny business centre for me, raised her intense black eyes and smiled benevolently.

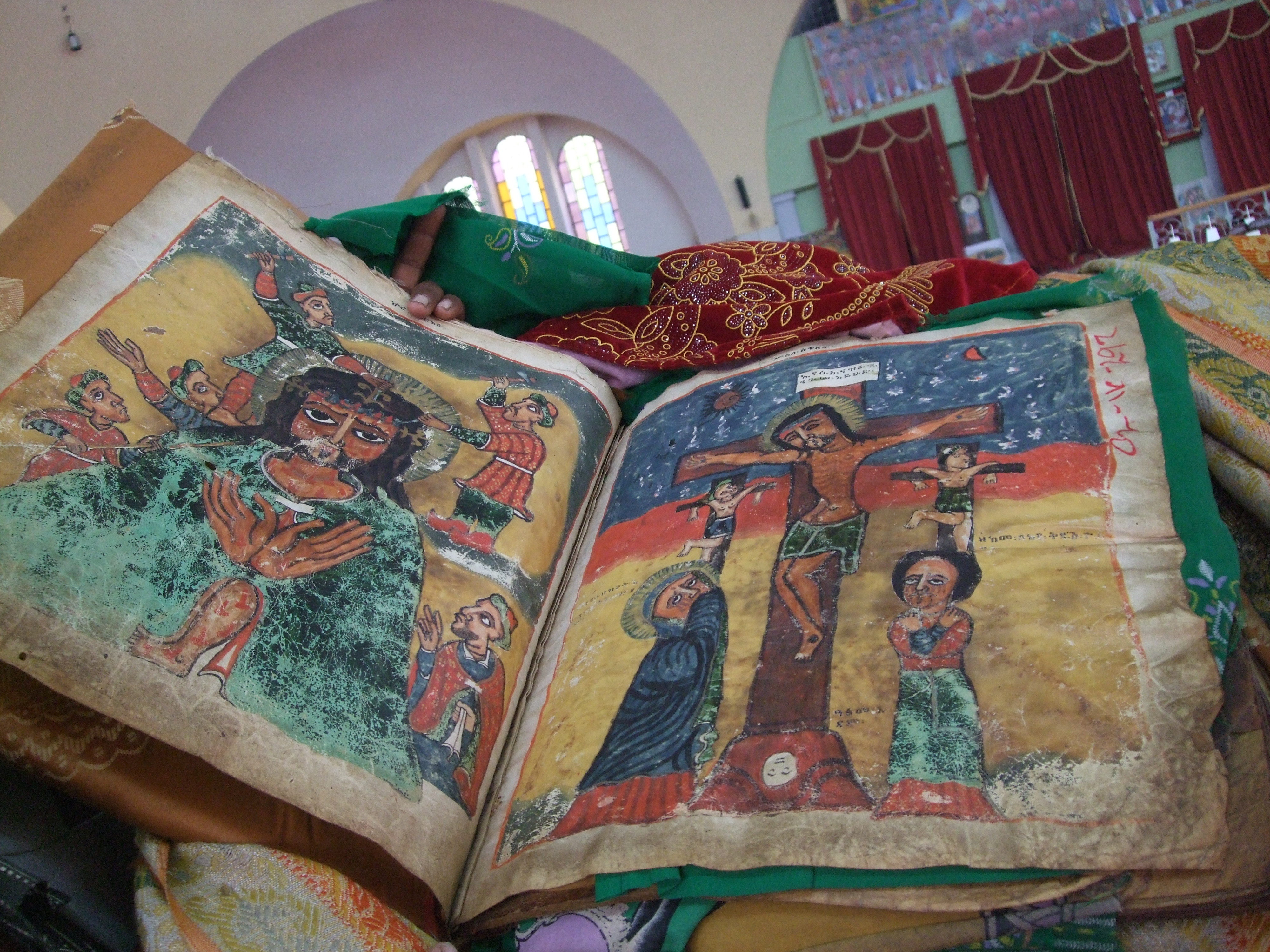

The Kebra Nagast is an Ethiopian orthodox scripture I had never heard of before coming to Ethiopia for the first time in 2010. Probably written in the eight century A.D., the sacred text supposedly explains how the Ark of Covenant ended up in Ethiopia. Or so I had been told.

‘THE GLORY OF KINGS,’ said the subtitle of the Kebra Nagast. ‘The interpretation and explanation of the Three Hundred and Eighteen Orthodox [Fathers] … concerning the greatness and splendour of ZION, the Tabernacle (tâbôt) of the Law of God, of which He Himself is the Maker…’

The Tabernacle, the famous Ark, I thought, feeling suddenly very hot in that cramped room.

‘And He said unto him [Moses], “Make an ark (or, tabernacle) of wood that cannot be eaten by worms, and overlay it with pure gold. And thou shalt place therein the Word of the Law, which is the Covenant …’

We were already late into the night, but I had convinced the receptionist to let me browse the Internet. This is something really pressing, I had explained. As pressing as getting to the bottom of one of the most puzzling mysteries in the Bible: what exactly is the Ark of the Covenant? Is it, as described in the Old Testament, a gold-plated acacia chest with magical powers? And if the Ark really existed, what happened to it? How could King Solomon have “misplaced” it?

I took a long sip of the delicious coffee that the attentive young woman had poured for me, savouring the strong taste of the local Arabica. I lit another dust-filled cigarette, wondering again how it was possible that the people who produced the best coffee in the world could sell such foul-tasting tobacco. Feeling on the cusp of a major discovery, I continued my reading on the flickering screen and scrolled through the two-hundred-page text, impatient to get to the turning point.

It had all started a few days before, in the northern Ethiopian town of Axum, when I approached the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, ruthlessly chased by local kids who were after sweets I did not have. An old man tapped on my shoulder.

“Be careful, young man,’ he whispered into my ears. ‘Here lies the Ark of the Covenant.’

‘Really?’ I said, ‘I don’t remember reading about this in the Bible.’

When he smiled, his black skin wrinkled like a gentle lizard’s.

‘It’s all in one book, the Kebra Nagast, but it was removed from the Bible by King James. Maybe European Christians were too afraid of the truth. For, this is not a legend; this is how it really happened.’

‘Can we see the Ark, then?’

‘Are you crazy? Not even our Emperor Haile Selassie was allowed to see it. Only the deacon, and he spends his entire life watching over it.’ Then he added with a straight face: ‘Don’t get too close or the deacon would kill you.’

He extended a book in a brown burnished leather cover, all written in Amharic script. Unfortunately, the Internet had yet to reach a small African town like Axum. Only in the Ethiopian capital, a few days later, would I be able to placate my questioning.

And so, I was now poring over the Kebra Nagast translated into Old English. Inside, I was supposed to understand how the Ark was spirited out of Jerusalem in 950 B.C. and transported to Axum in Ethiopia, by Menelik, the illegitimate son of King Salomon and the Ethiopian Queen Sheba. Here is what the Kebra Nagast had to say about the royal coupling:

‘And he [King Salomon] permitted her [Queen Sheba] to drink water, and after she had drunk water he worked his will with her and they slept together.’

When, at age twenty-two, Menelik finally learned about his origins, he decided to visit his philandering father:

‘He said unto the Queen, “I will go and look upon the face of my father, and I will come back here by the Will of God.”’

Towards the middle of the book, the title ‘How They Carried Away ZION’ hooked me. ‘Take the pieces of wood,’ God tells Menelik, ‘and I will open for thee the doors of the sanctuary. And take thou the Tabernacle of the Law of God, and thou shalt carry it without trouble and discomfort.’

Is that all? I thought. Surely, snatching away such a highly coveted religious artefact could not have been just a walk in the park. They must have sweat over it (especially with so many deserts to cross). I looked up from the computer screen and met the receptionist’s pensive gaze.

Apparently, Salomon had chased them. ‘And the King rose up in wrath and set out to pursue [them].’

But of course, Menelik was too fast for him. ‘And when the sons of the warriors of Israel saw that they had come in one day a distance of thirteen days’ march, and that they were not tired, or hungry, or thirsty, that they all [felt] that they had eaten and drunk their fill, [they] knew and believed that this thing was from God.’

Yes, sure.

There was even one passage to explain why nobody got to know, until much later, that the Ark had disappeared. ‘Let us set up these boards, which are lying here nailed together,’ Solomon orders the priests, ‘and let us cover them over with gold … and let us lay the Book of the Law inside it.’

Obviously, the Kebra Nagast was just another religious legend and not the historical account I had been expecting. Such a state of affairs certainly explained why Ethiopians made sure no one could see the (probably) fake Ark that they had built. I felt strangely disappointed, as if someone had claimed to have indisputable proof of God’s existence but handed me a copy of the Bible instead.

‘And chide ye me not because of the incorrectness of the speech of the tongue,’ said the writer at the end of the Kebra Nagast. Finally, no more beating around the bush. Well at least, I got to learn about King Solomon’s womanizing problems, I thought, while switching off the computer.

‘You look sad.’ I heard the receptionist say. ‘What happened?’

I told her what I had been reading all the while.

‘And you don’t believe we have the Ark, do you?’

I didn’t reply.

‘You think too much in your country. If you can’t see something with your own eyes, you don’t believe it’s true. Yes, we have the Ark,’ she smiled, ‘it’s here in our heart.’

I knew I had to come back to Ethiopia.

[1] Translation by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, 1922.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/kn/

OLIVIER CASTAIGNEDE: BIO

Born in France in 1973, Olivier has been living in Singapore since year 2000. In 2015, he decided to quit his salaried job in a multinational to focus on writing and traveling. His first novel, Radikal, set in Indonesia has just been published in September 2017 by Editions Gope:

http://www.gope-editions.fr/radikal.php

Currently enrolled in the first MA in creative writing in South East Asia, at Lasalle College of the Arts in Singapore, he also writes in English, mostly short stories and creative non-fiction pieces inspired by his trips around the world.